Tuesdays and Travels

I started this draft at 5:30 in the morning on Monday, waiting to board a flight in Delhi. I’m picking it back up to (hopefully) publish it as I wait for another flight at Heathrow, after three days at a data conference in London. This was my second time at this particular conference, and the fourth year running I’ve gone to a data conference in London in the fall.

This year was the first time I had to request an ETA for entry into the UK—not an estimated time of arrival, but an electronic travel authorization. Some weeks ago I downloaded the UK ETA app and used it to submit a scan of my passport, a scan of my face, and other information. I got the approval in my inbox almost immediately, but it was an extra step where in the past I’d been able to just land in the UK, walk through their automated gates with my passport, and be in. My arrival this year was the same experience, but only because the ETA on my passport was already in their system for this next year.

Why am I writing about data and passports? Well, fittingly, I just did some recreational data visualization on the topic as part of Tidy Tuesday, a weekly data project I’ve started participating in the month or so. The one from a couple weeks ago was on the Henley Passport Index, which measures the strength of passports based on visa-free access to other countries. The contributor of this dataset was inspired by an article about the strength of US passports declining. The US passport is still #10 on the rankings, but that’s down from #1 in 2014. So that news is pretty relevant to me, one of a generation of TCKs and now digital nomads who grew up thinking the world was our oyster—and a US passport-holder myself.

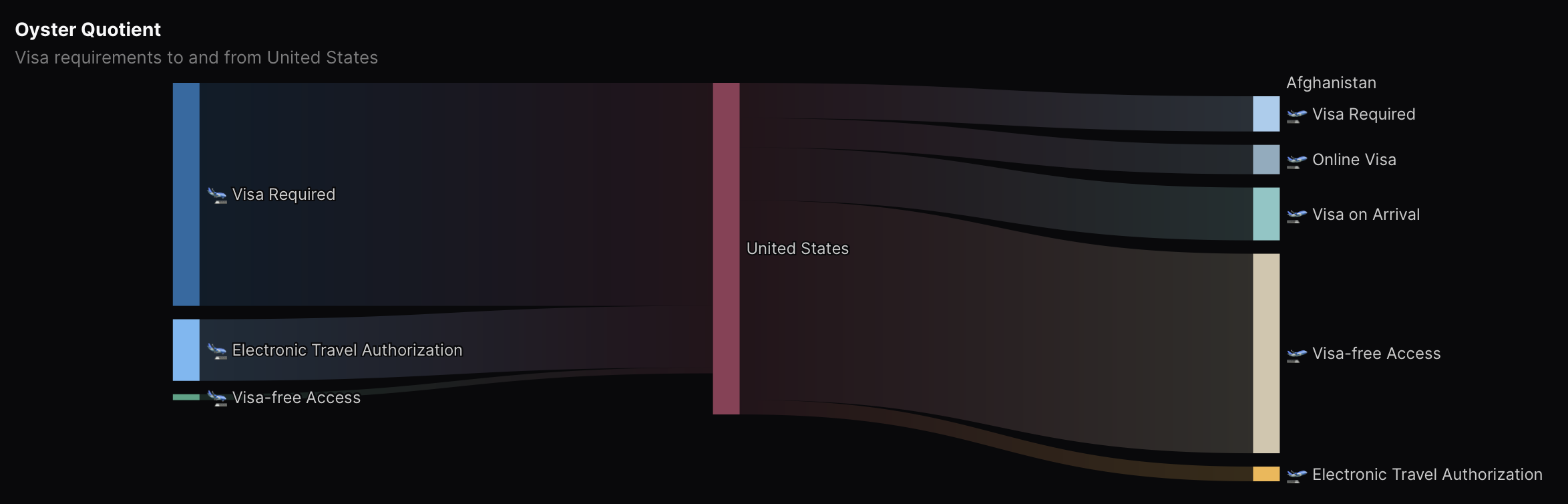

I could have done a visualization tracking the change in rankings over time as addressed in that article, but as I explored this dataset, I became more intrigued in looking at the data as a two-way street—essentially, how does access to a country for other nationalities correspond to the access granted to its nationals abroad? It took a few attempts to figure out how best to represent that, but I landed on what’s called a Sankey chart—typically used to represent flow. I set it up to show the breakdown of visa requirement categories as designated in the data—for entering a given country on the left side, and for passport holders entering others on the right. The page on my Tidy Tuesday site has an interactive version with a dropdown menu to pick the country. Here’s the US:

So I can see myself in that little slice of US passport holders applying for ETAs in one of 10 countries. But this also clearly shows what I was already pretty sure I knew: that while a majority of countries (at least for now) allow US citizens to visit with no visa at all—a privilege that I’ve taken advantage of plenty—an even larger majority of nationalities are required to apply for a visa to enter the United States. The number allowed to arrive visa-free? Four.

I wonder how many Americans would even think twice about this imbalance. Or how many would defend it?

This also doesn’t account for the difficulty of attaining visas, where visas are required.[1]

Anyway, I’d been wanting to write about these Tidy Tuesday projects since I started working through them, and then this particular one hit pretty close to home for me. There are a few other datasets up there too—including last week where I tried to look at bread (or more technically wheat/flour) and rice across cuisines.

You may have noticed it says “Global Variables” at the top of the page now. I’ve been sitting on that name for a couple months. I was going to tie it to a redesigned site, but while I haven’t gotten around to the redesign, this felt like an appropriate first post under that masthead. Global variables are, of course, a programming term, with an appropriate double meaning for someone like me—someone who, as I mentioned, grew up in a world that seemed increasingly connected and closer together—where “globalization” was only considered a positive word, bringing with it a literal world of opportunities. That starry-eyed optimism is starting to show some cracks in the cold light of reality—as countries around the world seem to be pulling away from that glimmer of a more interconnected globe. Megan and I still choose this life for ourselves and for our kids. We want to give them the same global perspective we had the privilege of growing up with. It is increasingly important as so much of the world pendulum-swings in the other direction. I hope something of that world survives long enough for my kids to experience it and learn from it.

Like, say, an H-1B visa. Just to name a totally random example. ↩︎